These days, .380 ACP pocket pistols vastly outnumber semi-autos in all the other so-called “mouse gun” calibers combined. But that’s a relatively recent phenomenon. In this edition of our ongoing Pocket Pistol Series, we’re looking at the history of .380 ACP and the pros and cons of .380 pocket pistols when compared to smaller calibers as well as subcompact single stack 9mm pistols. Watch the video below for details, or scroll down to read the full transcript.

Now that we have reached the 14th installment of our epic Pocket Pistol Series, it’s probably time that I get around to talking about the caliber that completely dominates this category of handguns: .380 ACP.

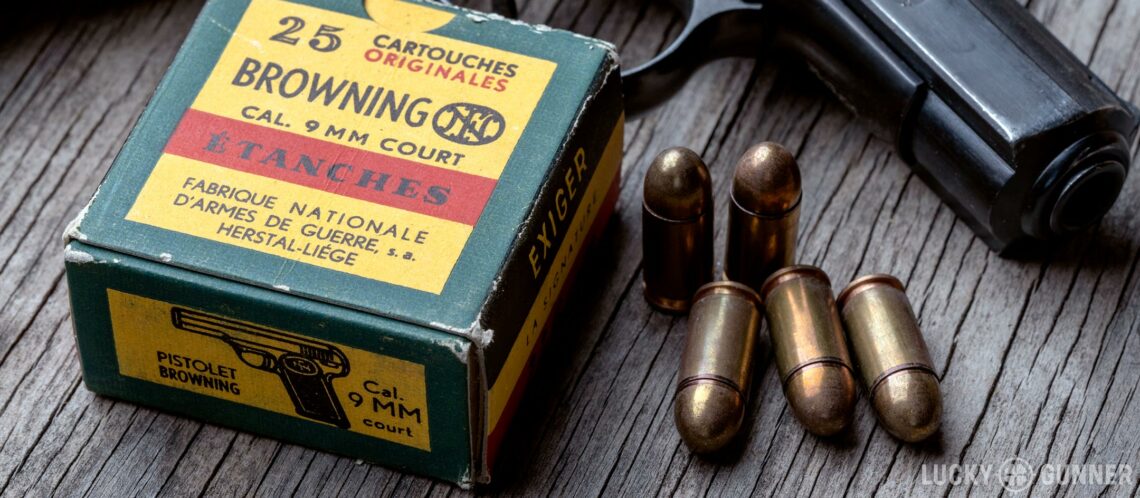

If you saw my video about .32 ACP a few weeks ago, the history of .380 ACP is going to sound really familiar. It was developed by John Browning in 1908, just nine years after he came up with the .32 ACP. The first .380 pistol was the Colt Model 1908 Pocket Hammerless which was a variant of the Model 1903 chambered in .32.

Like .32 ACP, .380 was more popular in Europe than in the United States. The Europeans have lots of different names for it like 9mm Browning, 9mm Short, 9mm Browning Short, 9x17mm, and 9mm Kurz… because the metric system is better and less confusing.

In the first half of the 20th century, .380 was widely used by military and police in Europe, in some cases replacing the .32 ACP sidearms they adopted just a few years prior. Back in the states, John Browning’s .45 Automatic was standard issue for the armed forces and law enforcement was dominated by revolvers, usually in .38 Special. .380s were almost exclusively used by non-uniformed civilians.

In the mid to late 1900s, the popularity of .380 ACP faded in the US, along with most other pocket pistol calibers. I think a lot of this simply had to do with the effects of urbanization. As people moved into cities and suburbs, carrying a handgun became a less socially acceptable thing for polite post-War Americans to do in many parts of the country. State and local laws restricting concealed carry became more common and existing laws were more strictly enforced.

On top of all that, in 1968, our wise and all-knowing Federal government passed the Gun Control Act. Among other things, this law created the federal licensing system for firearms dealers, it prohibited the sale of guns to minors, and most relevant for our discussion today, it created the “sporting purposes” standard for importing firearms. These new import restrictions were supposedly intended to slow the influx of what the news media nicknamed “Saturday Night Specials,” or low-quality, cheap, small caliber handguns that were frequently being used in crimes. Of course, the import restrictions did nothing to reduce violent crime, but 50 years later, we’re still stuck with a convoluted points system that handguns have to pass before they can be brought into the country. This essentially ended the importation of small handguns chambered for small cartridges like .380 and .32, regardless of whether or not they are either low quality or cheap.

So, by the time the modern concealed carry movement really got going in the 1990s, .380 ACP was not especially popular. As more and more states passed legislation supporting shall-issue carry permits, there was suddenly a new and rapidly growing market for small handguns. But 20 or 25 years ago, if you didn’t want to carry a full size or compact pistol, the standard go-to option was a snub nose 38. There were a couple of small .380s on the market, but they weren’t the tiny featherweight models we’re used to seeing today.

That all started to change in about 2003 with the release of a little pistol called the Kel-Tec P-3AT. Based on the success of their P32 in .32 ACP, Kel-Tec was able to just slightly scale-up the design and make it work for .380 ACP. With a polymer frame and a loaded weight of just 11 ounces, the P-3AT was by far the lightest .380 ever to go into production.

Kel-Tec sold a lot of these guns but demand for a new breed of pocket .380s didn’t really skyrocket until it was fueled by the power of a household brand name. In 2008, Ruger introduced the LCP — a tiny polymer-framed .380 that looked suspiciously similar to the Kel-Tec. Right away, the LCP was a hit for Ruger and in the last decade, they’ve sold over 2 million of them. In the meantime, other handgun manufacturers didn’t waste any time coming up with their own lightweight pocket .380s including Smith & Wesson, Taurus, Kahr, Sig, Beretta, Glock, and Remington. During this same time period, we’ve also seen the rise of the subcompact single stack 9mm pistols, which bridge the gap between pocket pistols and compacts.

What this means is that anyone who’s interested in buying a concealable handgun today has more options to choose from in a wider variety of sizes than at any time in the past. It’s good to have options but that also complicates the decision-making process. Let’s take a look at how the .380 pocket pistols as a general category compare to the alternatives. We’re going to consider the larger guns like single stack 9mms and on the other end, pocket pistols in calibers smaller than .380. I also wanted to compare .380s to snub nose revolvers in this video, but after thinking about it, there are just too many issues to cover and that topic really deserves it’s own video, so I will get to that sometime in the near future.

Compared to a single stack 9mm like the Smith & Wesson Shield, Glock 43, or the Walther PPS, the main advantage of a .380 is the smaller size. At a glance, they might not look significantly smaller, but for someone who wants to carry in a non-permissive environment, the .380s are more practical to keep 100% concealed all the time. They also tend to be much lighter. I did the math, and among the most popular models, the average loaded weight of a single stack 9mm was about 60% heavier than the average pocket-sized .380. That makes a big difference, especially if you want to carry the gun in a pants pocket, or in your waistband without a belt, or some other less conventional carry method.

On the other hand, .380 ammo is not as affordable as 9mm, there are far fewer self-defense loads to choose from, and of course the most common objection is that the round is not as powerful as the 9mm. And we’ll get to the issue of ballistics in a minute, but like I’ve pointed out many times throughout this series, in the context of personal defense for armed citizens, that should be a relatively minor aspect of the equation. The more important question is whether you can actually hit the target, and with the pocket .380s, a lot of people find that challenging. Frankly, most people don’t shoot the small 9mms very well either, but on average, they do seem to be a little easier to handle.

Of course, that’s going to vary a lot depending on the specific model and the person shooting. For example, I have a little more confidence shooting the 9mm Shield compared to the .380 Bodyguard. The Shield’s larger grip just makes more controllable. But, like most people, I shoot the Glock 42, which is on the large end of the spectrum for a pocket .380, a lot better than the 9mm Glock 43. So there is no hard and fast rule except maybe that for the lightest of the .380s — the ones that weigh around 11 to 13 ounces loaded — shooting them well is going to be a demanding task by just about any standard.

It’s easy to forget that the pocket .380s are not the smallest semi-autos around, either in overall dimensions or in the size of the caliber itself. Earlier in this series I’ve talked about pocket pistols chambered in .25 ACP, .22 LR, and .32 ACP. You could argue that the main advantage of the .380s compared to these other mouse guns is that it’s got superior ballistic performance. Again, I want to set that argument aside for a minute because I think the real benefit of the .380s in this case is simply their ubiquity. You’ve got many more options to choose from and they’re going to be easier to find whether you’re walking into your local gun shop or you want to order one online. That doesn’t mean those smaller calibers are necessarily a bad choice, it just means you might have to do some extra work to track one down and find a holster and other aftermarket accessories.

I can think of two main reasons you might want to go through that hassle to carry a sub-.380 pocket gun. The first is that for some reason, the .380s are just not small enough for what you have in mind. Maybe you want to pocket carry but you’re like me and you’re not a very big person and you don’t like big baggy pants, so you don’t have very big pockets. Even the smallest .380 might be pushing the limits of what you can comfortably cram into those pockets. Or maybe you’re like the guy who commented on one of our videos that a .25 ACP Beretta was the only gun he could conceal in his trunks when he went swimming at the YMCA. There are plenty of niche applications that might require something smaller than a Ruger LCP.

The other big advantage of the smaller calibers and one that I’ve talked about a lot previously is that they just don’t recoil as much as the .380s. With such a small amount of surface area to get a grip on, some people find that they can get quicker and more accurate hits with a pocket gun that doesn’t want to jump out of their hand as much as a .380 does. But, depending on the size of your hands and your level of manual dexterity, you might be just as likely to have trouble with one of these tiny pistols because there’s just nowhere to put your hands without making the thing malfunction or running into some other issue. If you’re worried about that but you still want the advantage of reduced recoil in a pocket gun, you might consider something like the Beretta 3032 Tomcat — it’s a .32 ACP and it’s very small, but the grip is relatively large.

So, only after we’ve considered all these other issues do I think it’s a good idea to factor in the terminal ballistics of these different calibers. If you start looking into the real-world anecdotal evidence of what .380 ACP is capable of, you will find a lot of people drawing the conclusion that it’s the minimum caliber that should be relied upon for self-defense and you’ll also hear that it’s a useless pea shooter not fit for killing mice and squirrels.

A few years ago when we first started our ballistic gelatin project, we tested 20 different .380 loads using a Glock 42 with a four-layer heavy clothing barrier on the gel. Just like we’ve seen with all the other pocket pistol calibers, these bullets either expand or penetrate, but they’re not very good at doing both. None of those 20 loads met the standard of 12 to 18 inches of penetration and at least 150% expansion. A couple of them look like they got pretty close if you look at the averages like the Hornady Critical Defense and the Sig V-Crown. But even those had at least two or three individual bullets fail to meet the standard and that’s with a Glock 42. A lot of the smaller guns have even shorter barrels which means less velocity and probably worse performance from these hollow points.

So if you want to judge these loads based strictly on the typical standards used in wound ballistics, there is not a .380 with performance on par with a good service caliber load like 9mm, .40, or .45. But that doesn’t mean they’re useless, either. With good shot placement, .380 is going to work just fine for personal protection in all but the most absolute extreme cases. I would prefer to rely on a round that’s got consistently good penetration even if it’s got unreliable expansion like the Hornady XTP. A non-expanding full metal jacket round with a flat tip might also be a good choice but we haven’t tested one of those yet. As always, whatever round you choose needs to work reliably in your gun and it needs to hit the target where your sights are aligned.

In the next installment of our pocket pistol series, we’re going to have a little .380 showdown and find out how some of the best pistols in this category compare to one another. In the meantime, if you need some ammo for your pocket pistol or any other gun, be sure to get it from us with lightning fast shipping at LuckyGunner.com.