It’s part three of our Lever Action Rifle Series! This time, we’re taking a good hard look at whether lever actions are really as reliable, dependable, and rugged as conventional wisdom would have us believe. Is a lever action the best rifle to have by your side for riding out the apocalypse? Or would you be better off with a rifle designed sometime in the last century? This is the third installment of our Lever Action Series. Be sure to check out the rest here.

Details in the video below, or keep on scrolling to read the full transcript.

Hey everybody, Chris Baker here from LuckyGunner.com. When I launched this series, I said it was going to be all about having fun with lever action rifles. That’s a little different than the other series I’ve done in the past. When I did my series on pocket pistols, shotguns, and revolvers, I was looking at them almost exclusively from the perspective of self-defense. I spent a lot of time considering the strengths and weaknesses of those different guns as life saving tools. Reliability is always a big part of that.

For the lever action series, the topic of self-defense is going to come up from time to time, but it’s not going to be the main focus. Even so, I want to tackle the issue of reliability, because this is an area where there seems to be a lot of common misconceptions. For whatever reason, lever actions have a reputation for being rugged, tough, and reliable. They’re the perfect gun for the prepper or outdoor survivalist. The truth is that, compared to almost any other rifle being made today, lever actions are more delicate and prone to failure.

I love lever actions, and we are going to have a lot of fun with them in this series. It’s not necessarily fun to focus on all the shortcomings of something you enjoy. But today I feel like I’ve got to do a little bit of myth busting. I’m going to give you five reasons why lever action rifles are not as reliable or durable as the prevailing sentiment might suggest.

1. Survivorship Bias

This doesn’t really say anything about the inherent mechanical reliability of lever actions, but I think it helps explain why they have such an inflated reputation. Survivorship bias is a logical fallacy where we tend to focus on the evidence that we can see and overlook the evidence we can’t see.

There are a lot of very old but still functional lever action rifles out there. That makes it easy to assume that lever actions are hearty, dependable rifles that last forever. But what we are not as likely to see are all of the broken and worn out lever actions that have been left to rust in the back of closets. Tens of millions of lever action rifles have been produced in the last 160 years. Even if 90% of them broke down and turned into dust, there would still be plenty of them floating around out there for someone to point to and say, “Nothing stops a lever action!”

We also, most of the time, don’t know a whole lot about how much these old rifles have been fired or what conditions they’ve been exposed to. Any rifle will last 100 years sitting in a gun safe as long as it gets oiled every once in a while.

Even regular use is not the same thing as heavy or hard use. Your granddaddy could have taken a handful of deer every hunting season with his .30-30 and still not have fired more than two hundred rounds total in a 40 year period. That gun may have been 100% reliable for him and what he wanted to do with it. If you took that same rifle to a cowboy action match or some kind of rifle class, it very well could choke within the first five minutes.

Part of the challenge of answering whether lever action rifles are reliable is understanding what we mean by “reliable.” Everybody has a different standard in mind. Generally speaking, our standard for reliability is much higher today than it was a few decades ago. We expect our guns to endure higher round counts and harsher treatment than our grandparents did. So just because you’ve got a lever action rifle that’s 50 or 60 years old and still functional doesn’t mean it’s the ideal survival rifle for the coming apocalypse.

2. Mechanical Complexity

A lot of people associate manually operated firearms with mechanical simplicity. A semi-automatic must have more moving parts and that means more things that can go wrong, right? But if you’ve ever taken a lever action apart, you know these guns are not simple.

There is a lot going on inside the action when you run the lever. And it’s all interconnected. Whenever one part moves, all the parts have to move, and they all have to move at the correct time and in the correct order. There are a lot of metal pieces rubbing against other metal pieces. If any piece of that puzzle, including the ammunition itself, is not just the right size and shape, the whole operation stops. You can have the tiniest burr or manufacturing defect in a single part and the gun will stop cycling altogether.

That mechanical complexity is part of why lever actions tend to be relatively expensive to make. It’s why reliability problems are difficult to diagnose and even harder to repair without a gunsmith.

If I wanted a gun that was mechanically simple, I would pick a bolt action long before a lever action. By comparison, bolt action rifles really are pretty straightforward machines. These days, even the cheap ones tend to work well most of the time. The magazine pushes up the rounds and you move the bolt back and forth to get them in and out of the chamber. That’s really all there is to the feeding cycle. Stuff can still break, there’s just not as many things to break as a lever action.

There might be other reasons to choose a lever action over a bolt action, but reliability is not usually one of them. A lever action is like a manual clockwork mechanism. Just because it’s reliant on manpower to cycle the action doesn’t necessarily mean it’s robust.

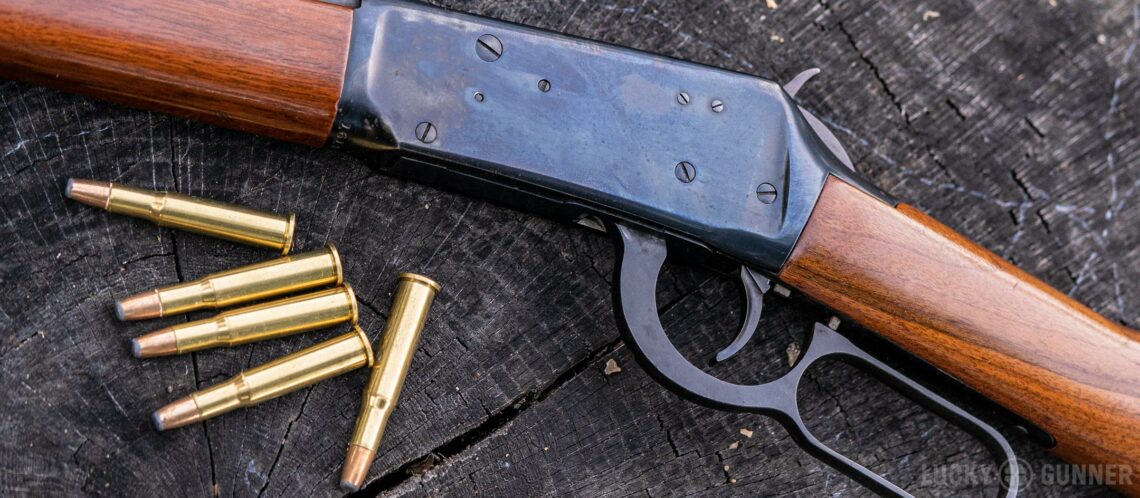

3. Screws Everywhere

A more specific aspect of lever action design that tends to cause problems is the liberal use of screws, especially in the receiver.

Screws and firearms don’t always play together real nice. The kind of forces and vibrations a gun is subjected to when it’s fired are the same kind of forces that often make screws want to unscrew themselves.

If I were to have a problem with this AR-15, the most likely culprit is the optic mount. That is the weakest link. So I put a witness mark on each screw with a paint marker so I can tell if any of them start to back out.

Same thing with this bolt action. The optic mount screws are probably the most likely part of the gun to give me trouble. Second would be the screws attaching the optic rail to the receiver. And third would be the screws attaching the action to the stock. If any of those begin coming loose, I’ll start to have problems with accuracy. But the gun will still function.

The screws in a lever action tend to have more mission critical jobs. And there are a lot of them.

Not including the screws on top for mounting optics or the buttstock screw, this Henry Big Boy has six screws just in the receiver. Most of the newer Marlins also have six screws holding the action together. The receiver of this Winchester Model 94 has nine screws. There are even more screws on these rifles, but it seems like the ones in the receiver are the screws that most often don’t want to stay put. And from what I’ve seen, it also seems like Marlins are more likely to have issues than other brands.

Sometimes, the screws will never give you a problem. With other guns, they seem to be constantly loose whether you’ve been shooting it or not. It never hurts to check the receiver screws to make sure they’re tight before and after a shooting session, or before you take it out in the field. You might also consider some thread locker if you’ve got a problem screw. I suggest starting with purple Loctite 222 because it’s made for small diameter screws like these. And remember, a little goes a long way.

To add insult to injury, the screws used in lever actions are usually delicate flat head screws that can easily be damaged if you use the wrong screwdriver. So you can’t just use any old screwdriver from the hardware store. You need hollow ground screwdrivers and they need to be the correct width and thickness for the screw. And keep in mind, each gun will have at least two or three different size screw heads. To tighten every screw on this Marlin, for example, I have to use four different screwdriver bits.

The new Marlin Dark Series rifles actually have Torx head screws in the receiver. I think that’s an excellent feature, especially if you value function over form. Everybody’s got a set of Torx bits and the screws are a lot harder to damage than the flat head screws.

There are some aftermarket thumb screws available to replace the lever screw for Marlin and Henry rifles. Wild West Guns makes this one and Ranger Point Precision has several different versions. Obviously, a thumb screw is a lot easier to check and keep snug without tools. The lever screw is also the only screw you actually have to remove in order to take out the lever and the bolt for cleaning and maintenance. But with or without the thumb screw, if you own a lever action rifle, you really should invest in a decent set of gunsmithing screwdriver bits for all the other receiver screws.

4. User-Induced Malfunctions

Any manually operated firearm is only as reliable as the person shooting it. With lever action rifles, there are numerous ways the shooter can introduce problems in the firing cycle. The most common, by far, is short-stroking the action. That’s when you don’t run the lever out completely until it stops, so the gun doesn’t get to complete that part of the cycle, and you end up with a failure to feed or failure to eject. Usually, this happens if you get in too much of a hurry or you’re not very familiar with the gun.

Some lever actions will not consistently eject if you run the action too slowly or too quickly. Some will not feed properly if the gun is not oriented just right. They rely on gravity working in a certain direction in order to feed, so if the gun isn’t parallel to the ground, or if it’s canted too far over to one side or the other, the cartridge might not feed on the first try.

Marlin rifles that have the crossbolt safety tend to mess people up. With most other rifles, if the safety is on, the trigger won’t move and that’s your clue that you’ve forgotten something. But when the Marlin the safety is on, you can still pull the trigger and the hammer will fall. The safety stops it before it hits the firing pin, but to the shooter, it looks like you’ve had a failure to fire. So you might just cycle the action and try again. You can empty the whole gun that way without realizing you’ve had the safety on the whole time.

It’s not uncommon to get a lever action that’s picky about what kind of ammo it will run. That’s not usually what we think of as a user-induced problem, but I’m going to include it in this category since the user is the one who chooses what ammo to feed it.

The most well-known example is probably the .357 and .44 Magnum lever actions. They are supposed to be compatible with .38 Special and .44 Special respectively, but a lot of guns are noticeably less reliable and less smooth with the Specials. If the overall length of the cartridge is too short, it might move around too much when it’s on the carrier and that can cause some hiccups in the feeding cycle.

Sometimes, it’s not just the length of the cartridge but the shape of the bullet that can have an effect on the feeding. Again, with the handgun cartridges in particular, this can be an issue. Some lever actions run a lot more smoothly with round nose full metal jacket ammo than with anything else.

Again, just because a gun is manually operated doesn’t make it inherently reliable. You still have to give it the right inputs so it’ll do what you want.

5. Intended Use

The lever action rifles made today are just not designed to be subjected to the kind of use and abuse that we take for granted that our modern semi-autos can tolerate.

I’m thinking especially of AR pattern rifles here, but really any rifle with a modern military pedigree was designed around certain considerations that were not even remotely priorities for for your lever action. Even if all you ever do with your AR is use it to put holes in paper and woodchucks, the design it’s based on has been tested and refined many times over so that it’ll go thousands of rounds without any need for attention from an armorer or gunsmith.

It was designed to be disassembled in the field with just a cartridge for a tool. It’s been tested in every extreme weather condition imaginable. It’s expected to maintain a certain level of accuracy even if the barrel heats up from continuous firing. There’s a whole industry of aftermarket AR parts that has been made possible because parts interchangeability was a mandatory requirement of the military.

None of that is true of a lever action. If you try to buy a replacement part for your lever action, you might run into that dreaded phrase, “hand-fitting may be required.” They don’t tend to work too well if they get dirty. You can’t do much to fix them without a tool box. Accuracy can go out the window just by resting the mag tube on something when you fire.

The very first lever actions that popped up around the time of the Civil War were made with military use in mind. Sometimes they’re even referred to as the original assault rifles. But even back then, a lot of people believed they were too fragile to be used in that role. They got better over time, but we haven’t exactly had 160 years of continuous evolution and improvement in lever action design. Most of today’s lever actions are still based on designs from the late 1800s.

And that’s okay. Because today’s lever actions are made with hunting and plinking in mind. They are really good at those things. We just have to have realistic expectations if we decide to start treating these guns the way we would an AR.

I want to finish up with a story I heard recently that I think summarizes all of this pretty well. This comes from Morgan Atwood. He said,

“I have two non-functional Winchesters — a 94 and an 1886 — that were my grandfather’s. They became his sometime in the 1940’s because he did gunsmithing for one of the large ranching concerns in the area which issued rifles. The practice was to bring him all the broken ones, and take back the best of the fixed ones. He retained the others for parts he couldn’t make (which were few).

In that world, at that time, those rifles were ubiquitous. And still required a skilled gunsmith and machinist to fix, with only some percentage being easy fixes.

Almost everyone who is into ARs has more parts for them just by nature of the hobby than my grandfather ever stocked for any gun in his gunsmithing days. And they’re easier to replace and get back into service, by far.

I wish “survival” oriented topics weren’t entrenched in this nostalgia for the “better times” that never actually existed.”

So there you have it. Lever actions are tons of fun, and still useful for some things. But when it’s finally time to emerge from your nuclear fallout shelter and rebuild society, you’re probably going to want an AR-15.