Since first detailing my adventures in searching for the ideal carry revolver in 2015, I have gotten a lot of questions about the 3-inch S&W Model 66-6 I eventually chose. Unfortunately, the 3-inch versions of this gun are pretty scarce, so it’s not something I’ve been able to recommend as an easy off-the-shelf option for other wheel gun aficionados. At SHOT Show this year, I got to take a quick look at what would seem to be the next best thing: Smith & Wesson’s new 2.75-inch version of the Model 66. I finally got my hands on one of these six-shooters a few months ago, and I have a some thoughts about S&W’s latest attempt at the mid-size magnum. The full review is in the video below, or you can scroll down and read the transcript.

The Smith & Wesson Model 66 Combat Magnum is one of my favorite revolvers ever, but they were tough to find for a while once production ended in 2005. Two years ago, Smith & Wesson re-launched the Combat Magnum with the slightly redesigned 4-inch Model 66-8. This year they added a 2.75-inch version that’s a little more friendly for concealed carry, and that’s the model we’re looking at today.

Every version of the Model 66 is a stainless 6-shot .357 magnum with adjustable sights built on the medium Smith & Wesson K-frame. It was first introduced in 1970 as a stainless steel alternative to the original blued-steel Combat Magnum, the Model 19. Both were extremely popular police sidearms through the last few decades of the 20th century. Like most revolvers at the time, the Model 66 was usually found with a 4-inch barrel although 6-inch and 2 ½-inch models were in regular production as well.

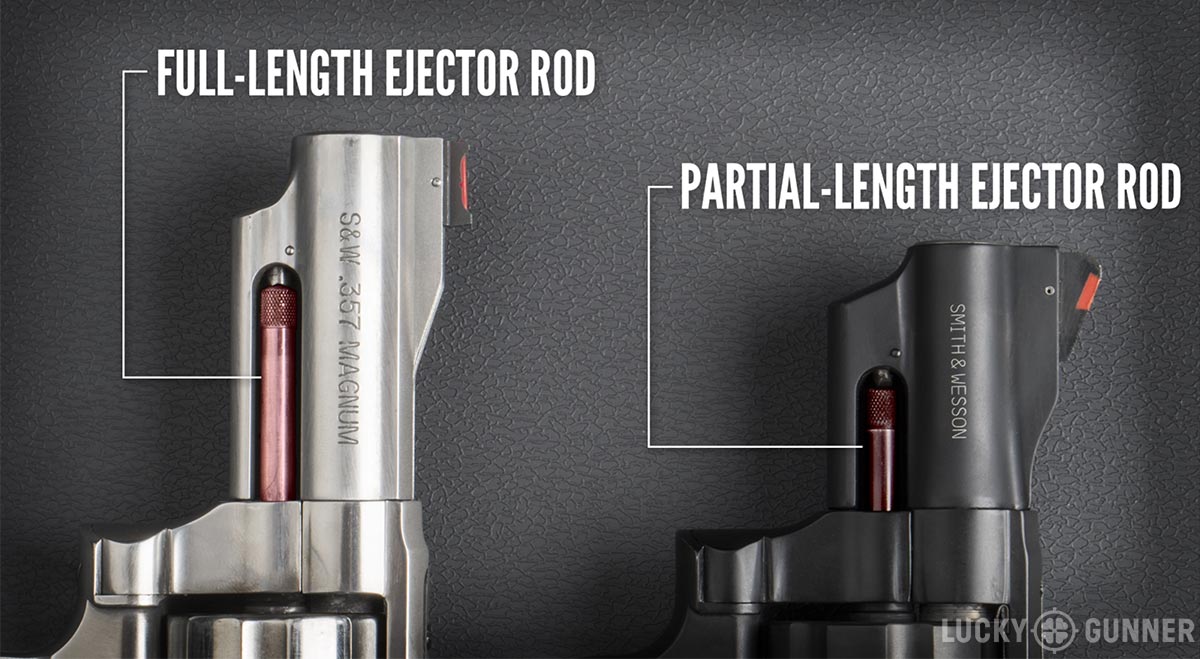

There were also some limited runs of a 3-inch model offered sporadically over the years, and that’s my favorite version of the 66. Some of you might have seen the video I did on my modified 3-inch Model 66-6 a couple of years ago with the somewhat tongue-in-cheek title, “The Best Revolver in the World”. I like the 3-inch barrel partly because it’s more concealable than the 4-inch, but still long enough to allow room for a full-length ejector rod. The old 2.5-inch models have a short ejector rod, which doesn’t eject all the empty casings quite as reliably when you’re reloading.

The new Model 66-8 also has a full-length ejector rod, even though the barrel is only 2.75 inches long, which is made possible by the new lock-up design. On the old models, the cylinder locks into the frame between a pin found in the center of extractor star and a second pin (called the “locking bolt”) below the barrel that locks into the tip of the ejector rod. So the barrel has to be at least as long as the ejector rod plus the spring-loaded locking bolt.

But check out the same spot on the new 66. There’s no locking bolt, and that’s because it’s been replaced by a ball detent on the frame that locks into the yoke. This is supposedly a more secure locking point, it allows the barrel to be a little shorter, and it also solves the occasional problem of the ejector rod backing out under recoil and locking the cylinder closed.

Just above that area, you can find a second design improvement. On the old K-frames, the forcing cone was flat at the bottom, and that was a weak point that would occasionally crack, usually after firing a lot of high-velocity magnum loads. The new forcing cone is thicker which should eliminate that weakness in the design.

| S&W Model 66-8 Technical Specs | |

| caliber | .357 Magnum |

| capacity | 6 |

| weight | 33.5 ounces |

| barrel length | 2.75 inches |

| sights | red ramp front sight, adjustable rear |

| action | double action |

| MSRP | $849 |

Unfortunately, while Smith & Wesson may have made some durability improvements, there is a lot about this gun I am not real excited about. Of course, it’s got the internal lock where the revolver’s soul leaks out. I’m not really a fan, but that’s old news. There are plenty of other issues to talk about.

Let’s start with the way it is configured. Traditionally, short barreled K-frames have been valued for handling and shooting like full-size revolvers, but in a smaller package that’s practical for concealed carry. But neither of these advantages are easy to see in this latest version of the Combat Magnum. The rubber stocks are large and cling to clothing, which compromises concealability. And the small rear sight notch and unreasonably heavy 15-pound trigger make the gun tough to shoot well.

The challenge of shooting the Model 66-8 was apparent when I ran it through our nine-stage Lucky Gunner practical handgun test that we have been using for all our reviews this year. My best score out of three runs with this gun was 47.87. That is the worst score out of all of the handguns I have tested so far, including a few small-frame snubbies and pocket pistols. Compared to my modified 66-6, I only dropped a couple of additional points in target penalties with the new revolver, but thanks to the smaller sights and the heavy, uneven trigger, I had to slow way down to get those hits, and my raw time was almost 10 seconds slower. [Note: A more detailed look at how the S&W 66-8 compares to the other handguns I’ve run through the test can be found on the Handgun Scoreboard.]

Mechanical accuracy testing was a little more encouraging. From a 25-yard bench rest, I fired two 5-round groups with each of 6 different loads in .38 Special and .357 magnum. The average group size was right around 2 to 3 inches for all but one of those loads, which is not bad at all.

| S&W Model 66-8 25 Yard Accuracy Test | ||

| load | avg. group size | avg. velocity |

| .38 Spl Winchester 148 gr Wadcutter | 2.2” | 679 |

| .357 Mag Speer Gold Dot 135 gr | 2.8” | 1147 |

| .357 Mag Remington 125 gr Golden Saber | 3.0” | 1216 |

| .357 Mag Winchester 125 gr PDX-1 Defender | 3.0” | 1252 |

| .38 Spl +P Winchester 130 gr PDX-1 Defender | 3.1” | 914 |

| .38 Spl +P Speer Gold Dot 135 gr | 5.0” | 914 |

My criticisms about how this gun is set up are mostly subjective, but there are also some quality control issues I feel obligated to point out. Smith & Wesson was kind enough to loan us this revolver to review, and this is actually the second one they sent. I had to send back the first one. Something was not fitted properly and a part of the yoke was rubbing against the frame, which made the cylinder really hard to open and close and even started to make the action feel a little sluggish.

When I told Smith & Wesson about it they apologized and quickly sent me this one. It has worked fine, but it’s also not exactly a perfect sample. There is a large burr on the cylinder release latch. Even though it’s just a cosmetic issue, this is the kind of sloppiness you don’t expect to see on a gun with an $850 MSRP.

With all of these complaints, you’d probably assume that I’m not recommending this gun. But really, it depends on what you’re looking for. If you want a new mid-size revolver that’s going to be ready to go right out of the box, I would not buy this one. You’d probably be better off with something like the 3-inch Wiley Clapp edition of the Ruger GP100. It’s a bit larger than the 66, but it’s an overall better execution of the mid-size carry revolver concept.

However, if you’re like me, and you just really prefer the size and the handling characteristics of the short barreled K-frames, the new model 66 might not be a bad starting point. My 66-6 is one of my favorite guns. But when I first got it, it wasn’t much different from this new one. It left the factory in 2004 — so it’s not exactly a shining example of Old World Craftsmanship. It has evidence of the same modern automation and cost-cutting shortcuts that Smith & Wesson revolvers have been criticized over for years. Even so, it’s still a fantastic shooter, I just I had to spend a little extra time and money on it. I think this new 66 has the same potential. To turn this into a decent carry revolver, at minimum, I personally would make the following changes:

I’d replace the oversized rubber stocks with something more concealable like Altamont wood boot grips.

I’d replace the mainspring with a Wolff Standard Weight Powerib spring to even out the double action trigger. There are better ways to improve the action, but the Wolff spring is a cheap fix that’s still a huge improvement.

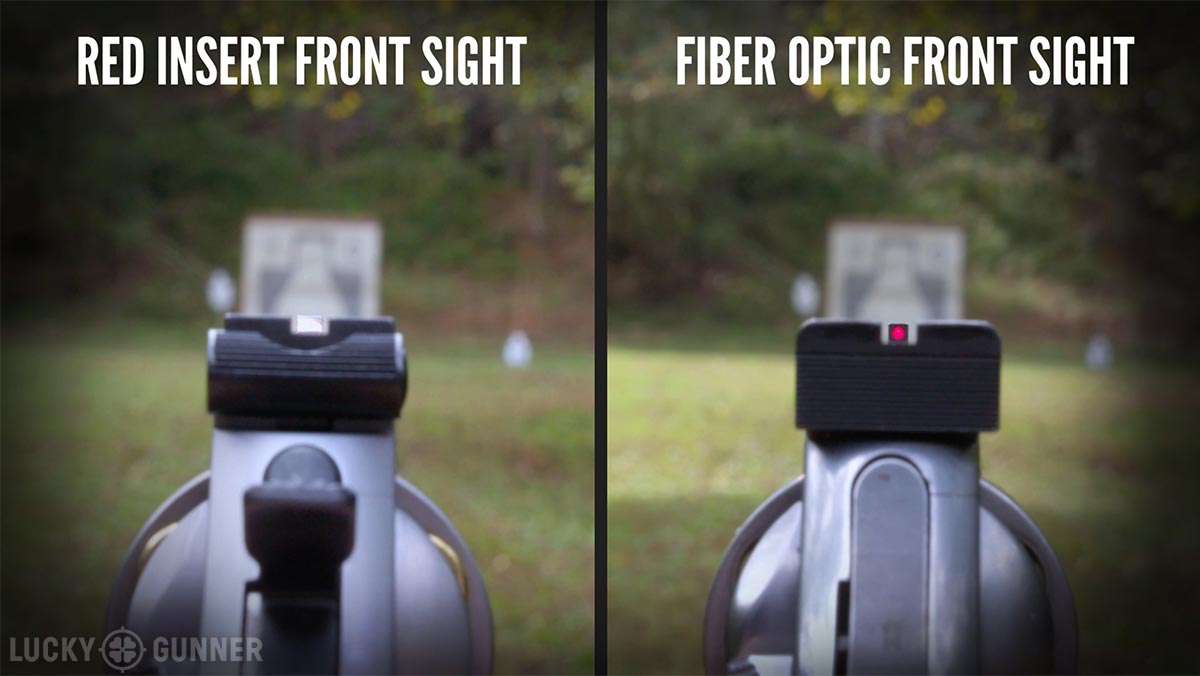

On the new 66, Smith & Wesson has switched to using a shorter rear sight blade. So the notch is shallower and it’s harder to pick up the front sight. I’d swap that out for a standard height rear sight blade.

And the front sight with the plastic red insert also has to go. They wash out really easily in a lot of lighting conditions and can be tough to see. An affordable upgrade would be a red fiber optic sight from Dawson Precision.

That’s a little over $100 worth of modifications on top of a gun that’s currently retailing for somewhere between about $700-775. Is that worth it for a modern S&W revolver? Again, it depends on your priorities. With an older pre-lock 66, you get something that looks and feels more refined and comes with pride of ownership. But you’ll need to plan to spend least $1000 if you want the 3-inch version with the full-length ejector rod, and you still might want to change the grips or the sights. With a new 66, you’ll save some money even after you fix it up, you’ll have better spare parts availability, and it might be a little more durable. So for fans of the K-frames, for the time being, you’re stuck choosing between the benefits of yesterday’s craftsmanship or today’s technology. It’s going to be really tough to get both.